Bourgeois civilization, now spread all over the planet, and which has yet to be successfully overcome anywhere, is haunted by a shadow: its culture, which appears in the modern dissolution of all its artistic means, is being called into question. - The Meaning of Decay In Art, Internationale Situationniste #3 (December 1959)

The cassette may now be a fashionable accessory to the fact of digital ownership or simply streaming music, but thankfully James Robert Moore challenges that comfortable scenario with this, a 'shadow' which haunts bourgeois hipsterism's fondness for things retro. In a wider sense, it challenges the cosy sound world most people like to cocoon themselves in, at which point I should stress that Noise as a genre is not something I gain much pleasure from. Yet as part of total sound and vision package, the two sides here make total sense.

If vinyl and cassettes were not so fashionable, one could argue that the return to materiality signals a desire for potential decay, for something more fragile than the digital medium. A new record today, however, is likely to be lovingly looked after rather than casually left out of its sleeve or lying on carpets to gain the scars of age common to albums from the time of vinyl. The nature of the tape, though, in my experience, is such that it can be chewed up, destroyed, at any moment.

Perhaps vinyl's popularity stems from the urge to simply play with the notion of potential decay in sound. We know how often the hiss and crackle of age is added to digital music as a gesture. Buying vinyl now is also a gesture, an acknowledgement of a past which many consumers never knew.

Punk rock revelled in notions of destruction and decay, whilst having no option but to join the material world of record production. It did it's best to undermine the material world of sleeves with cut'n'paste DIY art, but perhaps the ultimate Punk music was that which went unrecorded, except for private use. Punk's notional urge to embrace decay, to destroy, inevitably proved futile once it committed itself to product, thereby becoming a historical object prone to constant marketing, reclamation, revival and nostalgic reverence.

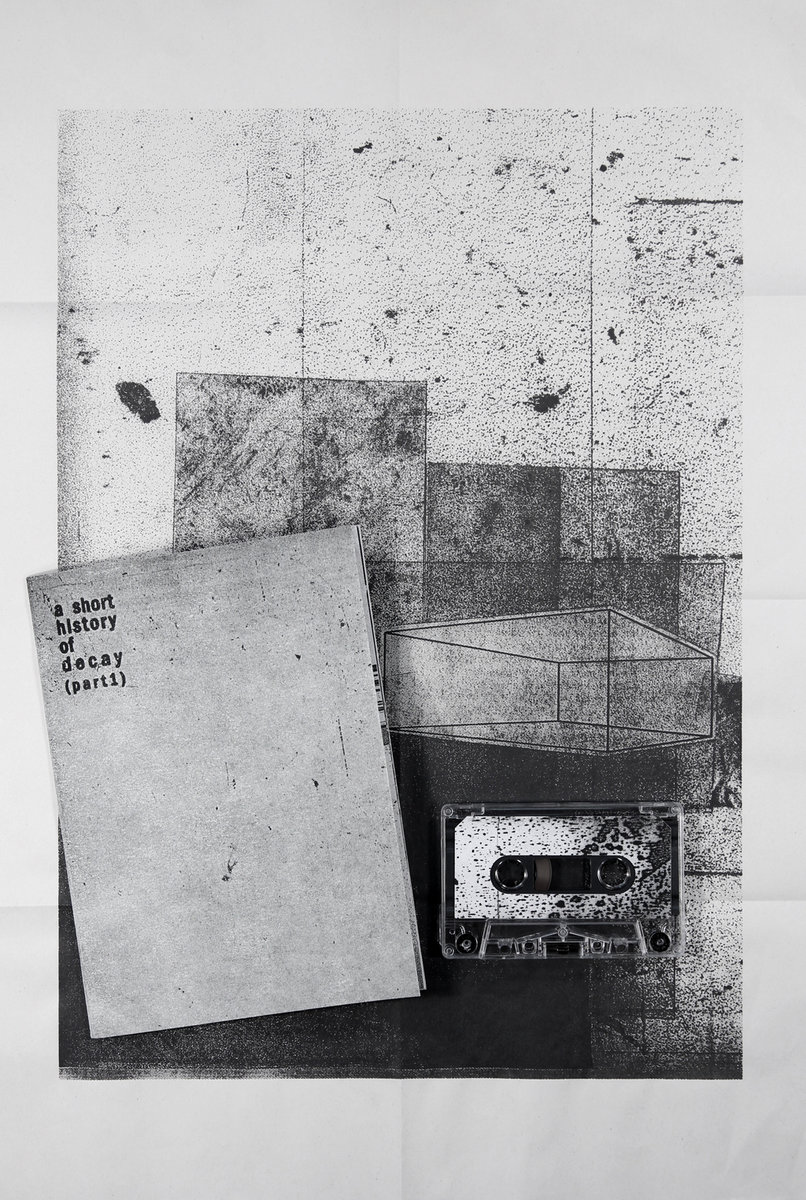

James Robert Moore's A Short History Of Decay will not go down in musical history, will not be written into that particular book. Neither will so much music made today, made for the world of instant availability, the pure pleasure of being accessible yet, as is so often the case, heard by few. This tape and booklet exists as only 25 copies. As I write, there may only be a few of those available. But it is not its scarcity that gives it merit, although there is great appeal in the limited; it is the product itself. Perhaps I should not use the word 'product', which implies a factory line large scale assembly.

Here is a booklet: center stapled, black and white images of decay and distortion which perfectly mirror the sounds. Xerox culture is another phenomenon which seems to be garnering interest amongst the new generation. More commonly, fanzine culture or small run magazines are reborn, frequently as part of the larger handmade/craft phenomenon and as such, sharing only the handmade/limited qualities in common with this, the shadowy side. Moore's booklet is a close relative of what we made in the 70s and further back, historical small press underground publications. As such, it is right, not only in keeping with the theory of decay, but the will to undermine bourgeois commodification and yes, even civilisation.

Such a small-scale creation screams loudly above the inane babble of insignificant, unimaginative products. It roars defiance and is a grand gesture, but more than that, a reality that can be held and felt if you're quick enough. Once in your hands it is more important still, a treasure which contrarily refuses to sparkle, to reward the buyer with the pleasures of glossier, more professional goods. Unlike those, the human hand is evident and we connect, instantly, with the artist.

As for the sound of decay, originally created for the B.A.S.S. sonic arts event at Framewerk gallery in Belfast, the processed field recordings made on a cheap recorder are as damaged as you would expect but deeply textured. In contrast to constant noise as an attempt to sonically batter you into submission, as heavy as much of it is, it is made more interesting by quieter passages, particularly on Side B where during one section it sounds as if a storm is gathering. At the eye of the storm it's as if objects are hurtling around in the approaching cyclone of sound. We might imagine or dream, for a moment, that it is the fabric of mainstream culture that is being torn to shreds.

Available here

No comments:

Post a Comment